4. Marvellous maps

Back in the last chapter, Izzy tried tracking information about the people assembled using some lists within another list:

iex> those_who_are_assembled = [

...> ["Izzy", "30ish", "Female"],

... a long time passes ...

...> ["Izzy the Younger", "Female", "20ish"],

...> ]

But as we can see here, the order of the items within the list can be input incorrectly due to human error. We need something that helps prevent human error like this, and if that something could helpfully indicate what each item in the list was — by giving it a kind of a name — then that would be good too.

For that, we can use a map. Just like a regular map, maps in Elixir can tell us where to find things, if only we knew where to look.

Let's look at how we could collect a single person's data using a map, using another random member of the crowd as an example:

iex> person = %{"name" => "Roberto", "age" => 56, "gender" => "Male"}

%{"age" => 56, "gender" => "Male", "name" => "Roberto"}

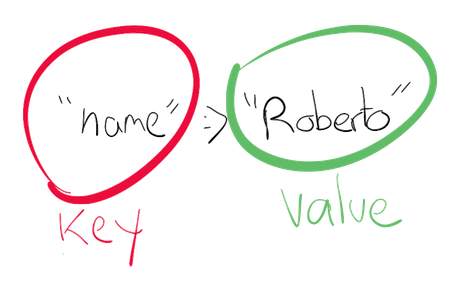

Maps start with a % and enclose their data in a warm curly-brace cuddle. In a map, we structure data

using keys and values. The thing to the left of the => is called a

key and the thing to the right is called a value.

Just like on a map of something like a city or a walking trail, a key here tells us where to find a particular value. If, for instance, we wanted to know the age of this person, we can use the key "age" to pluck out that value. We'll see that in a moment.

Unlike strings and lists where we can use a single character at the start and end to show Elixir where the starts

and ends are -- double quotes for strings, square brackets for lists -- we need to use that "curly-brace cuddle"

for maps. We need to use %{ to tell Elixir where a map starts and } to show where it

ends.

You might notice here that the computer has taken in our map and returned the keys in a different order to the one that we specified. The order of keys doesn't matter in a map at all, unlike in lists where order does matter. It would be pretty strange to spend all the time ordering the list only for Elixir to return it in a non-sensical order. For instance, if we had a list like this:

favourite_people = ["The Reader", "Izzy", ...]This list indicates that "The Reader" is the 1st favourite person, and that Izzy is a (close) second. The order here matters. For maps, it doesn't matter what order the keys and their corresponding values are in because the map would still be the same:

iex> person = %{"gender" => "Male", "age" => 56, "name" => "Roberto"}

%{"age" => 56, "gender" => "Male", "name" => "Roberto"}

The position of the "name" key within a map has no meaning. The keys for a map can be in any order.

You may now be thinking about how to get the data back out of a map once you've put it in. We talked about how to

"pluck" that value out before, but didn't see an example yet. In order to access a value from a map we need to

know the corresponding key. Once we know the corresponding key, then we can use [] to pluck that

value out of the map. Think of it like the claw from a skilltester, diving in to pick out the value.

Unlike a regular skilltester, these square brackets aren't rigged to drop the value mere inches from the chute;

these square brackets have an iron grip. For instance, if we wanted to get out the value of "name"

for person we can do:

iex> person["name"]

"Roberto"

And if we want to get the age, we would use the "age" key:

iex> person["age"]

56Izzy lets out a thoughtful "Mmmmmmmmmm" in something very close to an agreement. She likes maps. Now Izzy can know the exact data that we're collecting about the assembled masses, without a concern for how the data ordered, and then use that for later on. We don't know yet what Izzy has in mind for the data, but she's collecting it for a reason. Or at least, it seems that way.

To collect data about all the people assembled here before us, we can create a list of maps:

iex> those_who_are_assembled = [

...> %{"name" => "Izzy", "age" => "30ish", "gender" => "Female"},

...> %{"name" => "The Author", "age" => "30ish", "gender" => "Male"},

...> %{"name" => "The Reader", "age" => "Unknowable", "gender" => "Unknowable"},

...> ]As we can see from this example, lists can contain more than just numbers and strings: we can use maps too!

This list of maps containing the crowd's information is immune to the problem we were seeing at the start of this chapter. It doesn't matter what order the key-value combinations of age, name or gender are placed -- the maps will contain the right information at the right spots. As an additional bonus, we can refer to these values with their keys, rather than having to remember their positions.

Other types of keys

Before we go onwards, I'd like us to dwell a bit longer on maps. So far, we've seen that maps are comprised of a

series of keys and values. Those keys in our maps have only been strings, but the values have been a mixture of

strings (for name and gender) and numbers (for age). This kind of hints at

what maps are capable of storing, but I would like to cover a few more cases so we can really get the hang of

these map things.

Truth be told, in Elixir the keys and values can be whatever you wish them to be. Keys can be numbers, strings, lists, and more. Values can be anything as well. Let's say we asked ten people to pick a number within the range of 1 to 5. You can use number keys to represent the numbers that people picked:

iex> choices = %{

1 => 4,

2 => 1,

3 => 2,

4 => 2,

5 => 1,

}

%{1 => 4, 2 => 1, 3 => 2, 4 => 2, 5 => 1}Then you can very easily find out how many people chose the numbers 1 or 2 by using those skilltester-claw-like square-brackets:

iex> choices[1]

4

iex> choices[2]

1So as we can see here, we can easily use numbers as both the keys and values within a map and Elixir is totally cool with that. Just like we can use anything as items within a list, Elixir also lets us use anything as the keys and values within a map.

Now that we've established that, I want to introduce you to one more type of data within Elixir by way of a little code example. One common occurrence in Elixir code that you might see around is maps that look like this:

iex> person = %{

name: "Izzy",

age: "30ish",

gender: "Female"

}This is a short-hand way of writing:

iex> person = %{

:name => "Izzy",

:age => "30ish",

:gender => "Female"

}The keys in both these examples here are neither numbers, strings, lists or maps. But they look sorta like strings, right? So what are they? These keys are called atoms. They're a type of data in Elixir that is commonly used to represent names of things, like in this case. They're a simple name, and nothing more. We'll see a lot more of them as we go through this book, and so it's helpful to know what they are now.

Just as we were able to access values associated with strings and numbers, we can also access the values associated with atom keys by using the square brackets like this:

iex> person[:name]

"Izzy"

This is a little less typing than person["name"], and the way we define the map is a little shorter

too, and so it is generally preferred to use atoms over strings for keys within maps. This is why you might see it

a lot in other people's Elixir code too.

There's one more advantage to using atoms as keys over strings: we can use an even shorter syntax to read out the values:

iex> person.name

"Izzy"This is a full three characters shorter than any other way we've seen to work with a map. Typing less is always a good thing. And the code looks neater to boot without all that pesky punctuation.

So from here on out, we'll be using mostly atoms for keys within maps just because it's less typing and makes our code a little cleaner to work with.

And now to come back around to collecting information on who is gathered here today. For this, we can use a list of maps and have those maps have keys that are atoms, and values that are strings:

iex> those_who_are_assembled = [

...> %{name: "Izzy", age: "30ish", gender: "Female"},

...> %{name: "The Author", gender: "Male", age: "30ish"},

...> %{name: "The Reader", gender: "Unknowable", age: "Unknowable"},

...> ]Izzy excitedly disappears into the crowd again with this new map knowledge and starts collecting people's information again.